This is long, personal, rambling, and a week too late. There are so many better things your could read about Jobs than this. I’m posting it because I didn’t want to look back at this year on Prolost and see just a hole here. If you decide to read on, this is as good a time as any for me to humbly thank your for your attention.

In 1985, i was learning to program BASIC on an Apple II in my 8th grade computer programming class. I wrote a Death Star trench flight simulator that was every bit as impressive as my ability to not ask girls to the dance.

That same year, a friend whose father worked at the local university took me to a special room where they had a Macintosh. Instead of our usual skateboarding and lighting things on fire, we spent hours drawing Opus the penguin in Macpaint.

In film school I used Amigas for filmmaking, but when I graduated I bought myself a PowerBook 170 with a black and white screen. I felt I could afford it because I was working at my dream job, using a $40,000 Silicon Graphics workstation to create visual effects for movies like Twister and Mission: Impossible. On the latter, I met John Knoll, who showed me how he was using his Mac to recreate space battle shots for the Star Wars special edition.

He looked like he was having so much fun. My SGI workstation felt like an incredibly powerful computer. John’s Mac seemed like a limitless creative tool. I started taking my own time to learn After Effects, Electric Image, and Photoshop. I spent close to $10,000 setting up a pimped-out PowerMac at home. I started writing screenplays and dreaming up short films. After a year of learning how to be a post-graduate human, I was back to making my own movies with computers.

John Knoll started the Rebel Mac Unit at ILM and asked me to lead it. The systems guys took my SGI workstation away and replaced it with a Mac. For a minute, I panicked. I was about to bet my career on the theory that I could create ILM-quality effects using a computer and software that any idiot could buy.

We made space battles for Star Trek, displays for Men in Black, a minefield for Galaxy Quest, and hundreds of shots for a new Star Wars movie. We had jackets made with the Rebel Alliance logo on one shoulder and an Apple logo on the other, stitched black-on-black because there were people at the company who genuinely hated what we were doing.

When I saw the first digital video camera, the Sony VX1000, I bought it immediately. I got my hands on an early prototype of a FireWire card and put it in one of the two Macs I had on my desk (that was Rebel Mac’s version of a multitaksing OS). I started writing a short film that would be finished completely on a home computer.

The name “Rebel Mac” hearkened back to the stories of Jobs starting the Mac division at an Apple that had sprawled out of his control. But we couldn’t use it in public, because ILM had an exclusive PR deal with SGI that ended the year I quit that dream job.

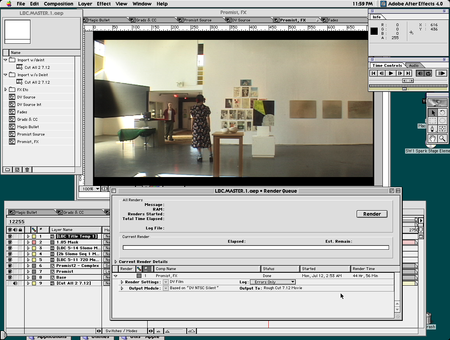

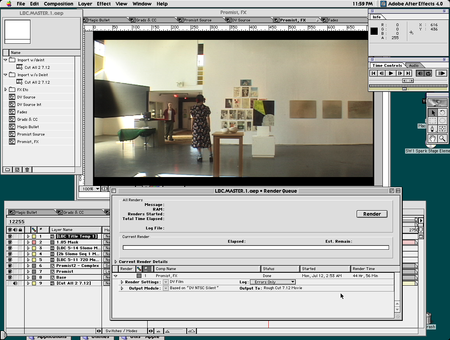

Rendering The Last Birthday Card in After Effects 4 on the blue G3 in 1999. Click to enlarge. Don’t miss the render time.

Rendering The Last Birthday Card in After Effects 4 on the blue G3 in 1999. Click to enlarge. Don’t miss the render time.

With my new blue G3 tower and version 1.0 of Final Cut, I finished my short and joined two friends in starting a company to make films and effects. We had grandiose ideas and “Lombard” PowerBooks. To promote our launch at the Sundance film festival, we made a promotional DVD with a pre-release version of Apple’s DVD Studio Pro.

We released version 1.0 of Magic Bullet. It was Mac-only and cost $999.

Our company grew, and our PowerPC-based Mac Pro workstations started to feel slow. We decided to switch to Windows, in part for access to faster Intel processors. Adobe and Intel worked with us on that transition, and I even took out an “advertorial” with them talking about our decision. We didn’t receive much in exchange for the promotion. Amidst rumors of a skunkworks division at Apple testing OS X on Intel processors, I had been considering writing a letter to Steve Jobs explaining the difficult position we were in. The advertorial was the easiest way to make sure he’d read it.

Apple responded by terminating our beta testing of Final Cut Pro, and retracting an offer to bid on the launch video for a new PowerPC Mac. I heard through a friend who got the video gig that Steve Jobs had referred to me as a “whore.”

I remember being so thrilled that he knew who I was.

Two years later at WWDC, Jobs announced that Apple would be switching to Intel.

That was 2005. Around this time, I was collecting my thinking about accessibility, creativity, filmmaking technology and post production into a book. It’s pointless to describe how essential my Apple laptop was to creating The DV Rebel’s Guide. Now you can read it on an iPad.

I directed the Second Unit on a movie in 2007. I had my 17” MacBook Pro with me every day. So integral to my process was it that the grip crew built a stand for it on my monitor cart. We called it the Nerd Station.

When we closed our company in 2009, I was once again left with nothing more than my Mac laptop. Now, when I walk into the offices of an executive who might be greenlighting the next phase of my career, it’s either that laptop in my hand, or my iPad.

Steve Jobs was instrumental in creating the tools that were not only the means of my creative work, they made me feel that there was no limit to what I could do. Everyone else makes computers for people who like computers. Steve Jobs made computers for people who like life.

He also made computers for people who can’t help but make things. When I’m working on the next Magic Bullet idea, there’s not a moment that I don’t try to imagine what Jobs would do in my shoes. How would he handle this idea, these products, this launch? On my best days I feel like I’m channeling a hundredth of a percent of his design principals—but in my own way, as he so eloquently reminded us.

As it happens, the day we all learned that Steve Jobs was gone, I had lunch at Pixar. A beautiful place full of amazing people using groundbreaking technology to do great work.

That’s the world I live in. That’s the world Steve left behind.

Shot with my iPhone 4 and processed in Noir for iPhone

Shot with my iPhone 4 and processed in Noir for iPhone

Sunday, November 6, 2011 at 11:00AM

Sunday, November 6, 2011 at 11:00AM