Blackmagic Cinema Camera

Wednesday, August 22, 2012 at 11:35AM

Wednesday, August 22, 2012 at 11:35AM The NAB 2012 announcement of the Blackmagic Cinema Camera (which folks are thankfully calling simply “the BMC”) from Blackmagic Design, the company that makes delightful video doohickies and acquired industry giants Da Vinci and Teranex, revealed a few interesting things:

- We are living in the “Chinese curse” age of cameras.

- In other words, disruption is the new norm. I’m not sure if there’s a static “game” to “change” anymore. So maybe we could all agree to stop saying that?

- Prolost is not a “camera blog.”

The so-called Chinese Curse goes “May you live in interesting times,” which certainly describes the landscape of digital cinema offerings available today. Apparently, we self-sufficient film folk now constitute a market worth serving directly. Where once we bent ill-suited cameras to our cinematic purposes (first all-in-one camcorders with tiny sensors and abusive automation, then DSLRs with near-accidental video functionality), now we can’t go a month without another “revolutionary” filmmaking camera competing to offer us something amazing at a previously unimaginably low price.

The question is, will these purpose-built offerings, such as the Kickstarter success Digital Bolex, the Sony FS–700, the 4K-ish Canon 1D C, and the KineRAW-S35 cure the DV Rebel of the urge to repurpose consumer cameras for their filmmaking efforts?

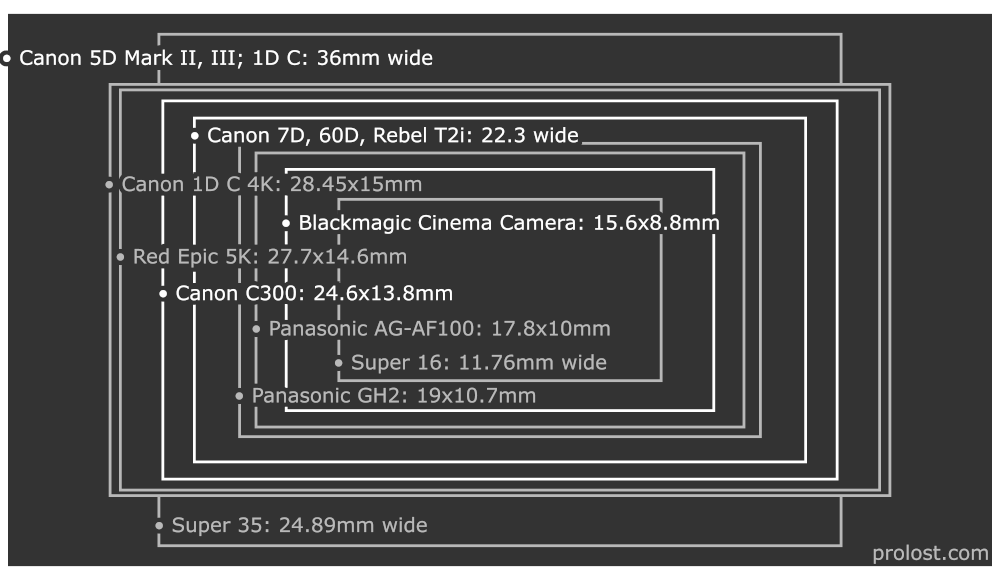

Blackmagic has seemingly (nearly) hit the “3k for 3k” target that many hoped Red would deliver, at a Micro–4/3-ish sensor size wandering between the 2/3” sensor many associated with the notion of a 3K raw camera and the increasingly ubiquitous and affordable Super 35mm size. If that seems like a decent deal, it’s worth noting that every BMC ships with full licenses of Resolve and UltraScope.

I was pretty busy when this camera was announced, but that’s not the only reason I refrained from comment at the time. I’ve gotten a bit weary of writing about unreleased cameras. Red has taught me to comb my writing for phrases like “the camera will have” and replace them with “the camera is said to feature,” and pretty soon I feel like I’m writing about nothing. But late last night, cinematographer John Brawley posted five test shots from a “production model” of the BMC to a brand-new Blackmagic forum. Brawley encouraged us to download the Cinema DNG sequences ourselves and have a play—so I did.

I love big-sensor digital cinema. I love shallow depth-of field. I’m fond of pointing out that sex appeal trumps tech specs every time. The interesting thing about the footage from this not-quite-cinema-sized sensor is that it is sexy. Not because of fetishistically shallow depth-of-field (although Brawley handily demonstrated that focus control is eminently possible with the BMC and some nice glass), but because it’s raw. I graded these shots in Lightroom 4. They came in looking a touch overexposed. I easily recovered the highlights and pushed these shots all over the place, but they never broke. After years of shooting with Canon HDSLRs to massively-compressed codecs, the rich neg offered by this little camera was beyond refreshing.

It’s easy to imagine that Blackmagic chose the smaller sensor to keep the price of the BMC down. It’s easy to get caught up thinking that maybe next, they’ll release a true Super 35 version of this rig. Or that the KineRAW at $6K might be worth the extra cost over the BMC.

But the challenge that befalls camera manufacturers is not to build the “perfect” digital cinema camera. It’s to capture the hearts and minds—and wallets—of filmmakers as much, or even more, as the wrong camera for the job keeps doing.

I think the Blackmagic Cinema Camera might just do that.

The Blackmagic Cinema Camera is available for pre-order now from B&H.