Space Monkeys, Raw Video, and Giving Us All You've Got

Wednesday, May 15, 2013 at 10:23AM

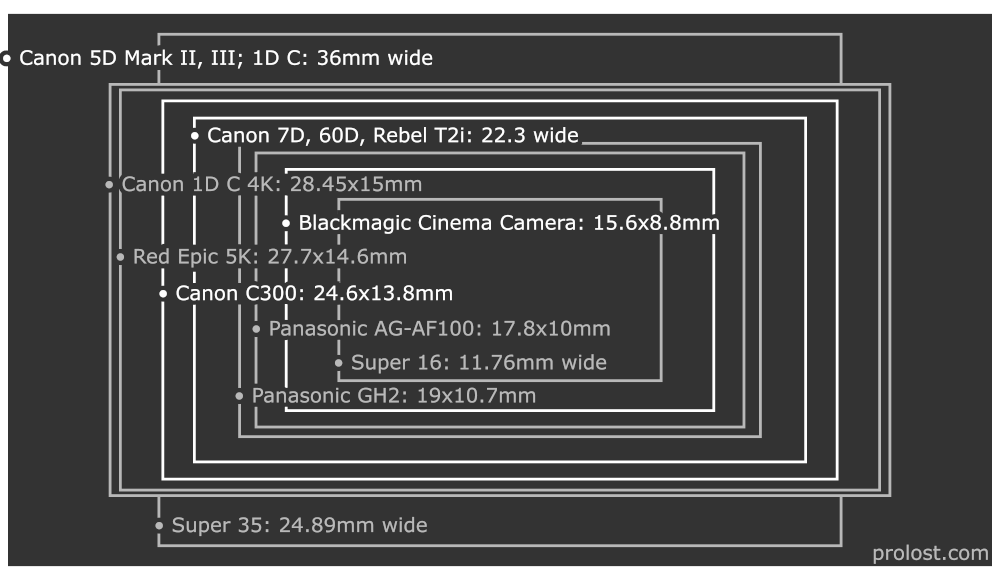

Wednesday, May 15, 2013 at 10:23AM The team at Magic Lantern have managed to hack the Canon 5D Mark III to record 14-bit raw 1080p video at 24 frames per second. The results are stunning—the highest-quality video we’ve seen from a DSLR yet, comparing favorably to images from cameras costing much more.

This is a big deal. But maybe not as big a deal as some have made it out to be. Like Ham, the chimpanzee that was launched into space on a Mercury rocket, the Magic Lantern raw hack is less notable for its discrete accomplishment than for what it portends.

How it Works

I was skeptical about the announcement of raw video at 1080p. This wasn’t a sensor crop, this was a full-frame image, somehow downsampled to 1920x1080—yet still being touted as “raw.”

How is this Magic Lantern thing “raw” if it’s scaled down from sensor res to 1080p? Scaling requires debayering. Debayered is not raw.

— Stu Maschwitz (@5tu) May 13, 2013

The answer came back from Magic Lantern themselves:

@5tu it’s not debayered, it’s 14-bit RGGB.

— Magic Lantern (@autoexec_bin) May 13, 2013

@5tu no idea, only Canon knows how the downsampling works. On 5D3 there’s no moire, on 5D2 there is.

— Magic Lantern (@autoexec_bin) May 13, 2013

Put this way, it makes sense—and matches what Magic Lantern said in their original post:

Key ingredients:

- canon has an internal buffer that contains the RAW data

Of course. Canon sparsely samples the sensor (the popular theory is that they skip lines and bin rows) to create their own 1080p bayer image, which they rapidly debayer to create 1080p video frames. It looks like Magic Lantern have found a way to grab this raw buffer and save it directly to the CF card.

Whatever magic Canon worked to eliminate the moiré in the 5D Mark III’s video now benefits Magic Lantern users as well. And whatever downsides there are to this sparse sampling will also affect the raw hack.

What it Takes

Right now, the hack requires quite a bit of work to get up and running, and even more work to derive useable results.

But those usable results are compelling. There are tremendous opportunities afforded by the raw video hack over the compressed H.264 recordings the camera natively makes.

- Post-processing debayering can be much better than the hasty in-camera processing. The much-lamented softness of 5D Mark III video is improved noticeably by handling the debayering (including noise reduction) after the fact. Although I can’t help but wonder if we’d get even better results from a demosaicing algorithm tuned to the specifics of the 5D’s subsampling pattern.

- The 14-bit raw frames contain a great deal of dynamic range that 8-bit, heavily compressed video does not.

- No compression.

But there’s a price to pay for recording 14-bit uncompressed raw. It requires crazy-fast CF cards, and you’ll only get 15 minutes of video on that 128 GB card, according to Cinema 5D, who graciously posted their workflow and samples, “after struggling for a day” to get it all working.

What it Means

Even once the setup process is streamlined, and the raw-to-DNG conversion process is streamlined (or eliminated), uncompressed raw video is probably not the best option for most DSLR shooters. Better would be something like ProRes or DNxHD—but that would require high-quality debayering in the camera, which would seem to require more processing power than the 5D Mark III has to offer. More processing means more heat, which means a very different camera design than an SLR. It’s easy to see why digital cinema cameras start to get expensive.

The 5D Mark III raw hack is cool. It’s important. It’s something we’ll use, and like, and get good results from. But as exciting as it is today, it’s even more significant for what it means for the future of low-cost digital cinema cameras.

Mr. Ham risked his furry life to prove that a primate could flip switches in space. Three months later, a human being took the same trip. By proving that raw video is possible from the 5D Mark III, Magic Lantern have joined the forces pushing the industry in an important new direction.

Five years ago I wrote that large-sensor video had shown “that it’s no longer OK for manufacturers to make a video camera that doesn’t excite us emotionally.” Since the industry did such a good job of heeding that advice, my new mandate for the future is this:

It’s no longer OK for cameras not to give us everything they’ve got.

What I love about the new generation of cameras, such as those from Blackmagic, Red, and even GoPro, is that they all give you everything they’ve got. They’ll give you the highest image quality they can, in the smallest package possible. They’ll compress images as much or as little as you want. They’ll max out their resolution at the expense of frame rate, or vise versa—whichever you like. And they’ll pack their best dynamic range into any format they can record.

Compared to this, Canon and Sony’s digital cinema product lines seem cruelly restricted at every tier. The result was palpable at NAB. As I said on stage at the SuperMeet, the show seemed to belong to camera upstarts. To cameras from small booths. From the Phantom Flex4K with its Super35 4K at 1,000 fps, to the Digital Bolex, the exciting cameras at every price point were the ones not charging by the button, feature, or codec, but simply giving you all they could do.

What Magic Lantern have done is show camera makers that if they won’t give us all they’ve got, we’ll just take it anyway. The smart manufacturers will try to beat us there out of the box.