What I’d like to see in a Lightroom iPad Companion App

Saturday, March 31, 2012 at 5:34PM

Saturday, March 31, 2012 at 5:34PM

I get the sense that Adobe is thinking a lot about tablets and Photography. They’ve released Photoshop Touch for iPad, as well as Carousel Revel, which is like a cloud-based Lightroom-light that syncs across mobile and desktop platforms.

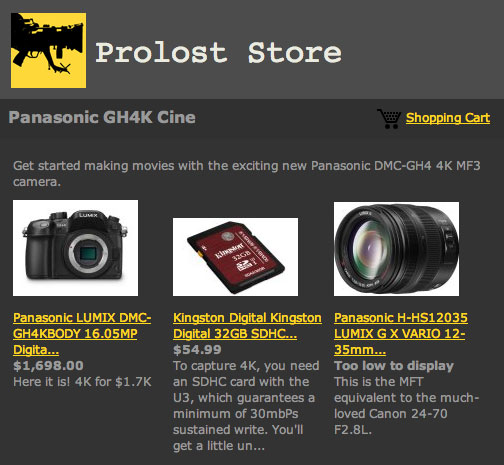

Third-party Lightroom users have also tried to bolster their own photo management experience by creating companion mobile apps. LRPAD turns your iPad into a touch-based control surface for Lightroom’s Develop module, and Photosmith acts as an in-the-field pre-processing companion to Lightroom, allowing you to begin sorting, tagging, and rating photos even before adding them to your Catalog back home.

I’ve tried most of these apps, and while each of them seems logical and desirable on the surface, in actual use, none of them turn out to be what I actually want from a tablet-based augmentation of my already awesome Lightroom experience.

Housekeeping at the DMV

The work I do with Lightroom on my 27” display, at my comfortable desk, a cup of something delicious at my side, leaves little to be desired. I don’t feel a huge need to tweak develop settings on an iPhone screen, or do a bunch of metadata work in a cafe somewhere as a prelude to proper importing. How many 5D Mark III shots can I really import into my 64GB iPad? How fast will that process be? Whatever the efficiencies of organizing on-the-go might be, they seem more than obviated by the exponential increase in speed and efficiency I’ll have at home on my optimized system.

What I want from a mobile Lightroom companion is a way to utilize whatever idle time I might have here and there for productive work on my main Lightroom Catalog. I don’t want to send new photos to it. I don’t want to adjust exposure and color temperature. I just want to do what I never seem to have enough time to do at home: housekeeping.

Imagine standing in line at the DMV and using that time to add keywords to your photos from yesterday’s shoot, rather than playing Angry Birds.

Imagine you find yourself standing at a spot where you’d once taken a great shot. You whip out your phone, search for that photo in your Lightroom Catalog, and add your current GPS coordinates to the metadata with one tap.

Imagine having your entire Lightroom Catalog available for browsing and search wherever you are. You’re at brunch with your Mother-in-law and she asks you about that great photo of her and her grandson you made recently. You show her your phone and say “This one?” When she identifies it, you add it to a new Collection called “To Print For Mom” right then and there.

When I’m sitting in front of my big, beautiful iMac screen, I’m inclined to spend my time developing my photos, making them look their best. Not sorting, deleting bad shots, adding keywords, and organizing them into albums. But when I’m stuck somewhere with my phone or iPad and little to do, that’s exactly the kind of busy work I’d love to be able to pick away at.

But That’s Crazy

No, it’s not.

If there’s anything Adobe’s pushing harder than tablets these days, it’s their Creative Cloud thingy. Haven’t heard of it? That’s because it’s not all that useful. Yet.

My Lightroom Catalog, which manages 11 years of active digital photography and over 130,000 shots, is 1.6 GB. That’s just the Catalog—not the photos. 1.6 GB of thumbnails and metadata. Every night this file gets backed up to a local hard drive and to Backblaze (which is unquestionably the best cloud backup solution for photographers—seriously, do it). Some people even keep their Lightroom Catalog file on Dropbox. Even my gargantuan file would fit with the 2GB that Dropbox offers for free.

Although a Lightroom Catalog appears to be one megalithic file, it is actually a package containing many smaller sub-files, few of which are likely to be changed in a typical editing session. This means that it can be synced or backed-up incrementally, for much smaller data transfer rates.

What I imagine Adobe could do to facilitate my dream of accessing my Lightroom Catalog everywhere, is implement a Backblaze-like trickle-up syncing system. It would take a while to complete at first, working in the background whenever Lightroom was open. But after that initial sync, further updates would be relatively painless. Lightroom could warn me on quit if it wasn’t done syncing my changes, giving me the option to let it finish silently in the background before terminating.

Of course, Lightroom is only syncing my Catalog file itself, not the huge camera-original files. But along with the folders, filenames and metadata, it would also upload a small thumbnail file, to facilitate my mobile browsing.

The uploading would not be the hard part. As with any such system, the tricky aspect might be the syncing. Lightroom would have to be able to combine my local changes with those made via the mobile companion app, and possibly provide a UI for resolving sync conflicts.

Not so fun, but totally worth it. Lightroom would not only be providing its users with an excellent off-site backup plan for their valuable Catalog files, it would be giving them a truly useful mobile workflow that could transform spare moments into better photo organization.

People pay money for those kinds of things.

Busy Work is Welcome When You’re Not Busy

At The Orphanage, there was a brief period when we used a node-based compositing system that wasn’t Nuke. This application did not seem to separate its rendering threads from its UI processes, so compositors could not move or organize their nodes while waiting for their images to update. The result was that their node trees were a spaghetti-like mess.

This wasn’t because the app was slow (it wasn’t), it was simply due to human nature. When the app is done processing a frame, the artist sees the result of their last adjustment, and what they want most to do right then is respond to that by making another creative tweak. There nevrer seemed to be a good time to pause and clean house.

Nuke, on the other hand, allows the artist to freely move nodes around while the image is rendering. Again, Nuke is fast, so we’re not talking about a huge amount of time here—just hundreds of brief little windows of opportunity during a day when tidying up a node tree is so easy to do that, well, why not? There’s not much else to do while waiting those few seconds for the frame to update. Even our messiest compositors became compulsive neatniks in Nuke.

This is how I feel when sitting at Lightroom. Why should be I tagging when I can be brushing in local exposure adjustments? But catch me at the dentist’s office and heck yeah, I’d rather spend that time tidying up my Catalog than aiming enraged avifauna.

The slogan of Adobe’s Creative Cloud initiative is “Everything you need, everywhere you work.” Sounds great Adobe. Let’s have it.