Write Better With Fountain

Thursday, March 8, 2012 at 12:09PM

Thursday, March 8, 2012 at 12:09PM Integrated Story Outlining in Plain Text

What you set up with the inciting incident…

What you set up with the inciting incident…

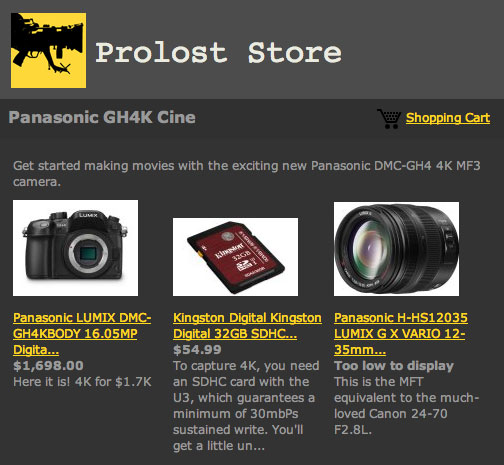

The simplest way to begin screenwriting with Fountain is to open any text editor and start typing something that looks like a screenplay. You can then send that file to the free Screenplain web app to turn it into styled HTML, or a Final Draft file. You could also import the file into Fade In or a growing number of screenplay apps that support Fountain. Soon you’ll also be able to use Highland to convert a Fountain file directly to a printable PDF.

But if you’re just getting started with Fountain, you may like some assurance that your text is being interpreted correctly. And even a seasoned Fountain writer could benefit from a bit of WYSIWYG.

Marked for The Kill

Enter Marked. As I’ve mentioned, Marked is a simple and powerful HTML preview app for writers using the popular Markdown syntax that inspired Fountain. Marked is flexible enough to be configured to use other syntaxes—so Marked, combined with the Screenplain engine and some custom CSS, becomes a live preview tool for writing in Fountain. Use whatever text editor you like. Every time you save, Marked will update, showing you what your screenplay will look like.

Click to enlarge. Don’t make me say it for all of them.

Click to enlarge. Don’t make me say it for all of them.

Simple enough, and a great way to get used to working with Fountain. And there are some nice perks to Marked, such as the navigation pop-up that shows you each of your Scene Headings in a menu. That feature, while handy, suffers from a common screenwriting software pitfall: Scene Headings are often not a very useful way to navigate a script, as they don’t necessarily line up with what we think of as the beginnings of actual “scenes.” What you or I might consider a single “scene” might contain several Scene Headings.

Outliners

Organization and structure are such an important issues that I made sure Fountain had some provision for supporting them. Fountain’s Sections are invisible, hierarchical markers that you can use to demarcate the structural points of your story—or anything else you like. Synopses allow you to annotate a Section—or a Scene Heading—with non-printing descriptive text.

You can add Sections and Synopses to your Fountain screenplay as you work, or as a part of rewriting. You can also begin the writing process with them. You can use them to denote scenes, sequences, act breaks, or whatever is helpful to your writing process.

Every writer is different, but most utilize some method of outlining their story—usually in a completely different app, or in no app at all (3x5 notecards are a popular meatspace method). My problem with those techniques is that they’re not writing. When I’m several days into the road trip of my story, those disconnected outlines feel like a map locked in the glove compartment of the car we decided not to take.

Fountain fixes the disconnect between the outlining and writing process. You can begin your outline as a text file using Sections and Synopses, and then seamlessly fill in bits of the actual screenplay as they come to you. All without your hands ever leaving the keyboard, all in whatever text app you prefer, on whichever platform.

That last bit is important: Although you may not see yourself writing an entire screenplay, or even a scene, on a tiny device such as your phone (yet), I bet you could imagine jotting down an idea for an outline there.

Sections and Synopses: The Syntax

A Section in Marked is exactly like a Header in Markdown: you simply precede it with any number of pound signs. The more pound signs, the more “nested” the Section:

Synopses follow Sections or Scene Headings and begin with a single equals sign.

Screenplain and Marked will display your Sections and Synopses in HTML, using a lovely style sheet created by Jonathan Poritsky. Of course, they are not meant to be included in printed output, so Screenplain ignores them when creating a Final Draft file, as will Highland. But seeing them while you write is nice, and reminiscent of Movie Magic Screenwriter’s integrated outlining features.

And that navigational pop-up in Marked? It displays your Sections, indented according to hierarchy, and allows you to navigate by them. Scene Headers are still there as well, nested below Sections.

This behavior is also available in some Markdown editors. MultiMarkdown Composer, for example, displays your headers as a live, nested Table Of Contents on a side panel.

Writing Kit for iOS also has this Header-based navigation built in.

To demonstrate how an outline might look in Fountain using Marked, I whipped up a quick outline of Die Hard using only Sections and Synopses. Even in plain text, this document is readable and clear. In MMD Composer, the structure is navigable via the TOC panel on the left. And in Marked, the outline is presented in a clean, attractive layout.

And here’s what it would look like if Jeb Stuart had started writing his amazing screenplay right within this hypothetical outline:

If you’re the kind of writer who likes to work with a general-purpose structural guideline, Fountain’s Sections and Synopses are perfect for you. Much to the chagrin of seasoned writers everywhere, you can begin your writing with a template. Here’s the well-known Save The Cat beat sheet in Fountain format:

Or maybe you’re the anti-structuralist who poo-poos “templates” and even rejects the classic three-act structure. You can still use Sections as simple bookmarks to mark important beats and make navigation easier.

Story Arch

…you must pay off at the climax.

…you must pay off at the climax.

Sometimes, when writing, I feel that my story is too unwieldy to grapple with. It’s composed of thousands of tiny details, and yet they must all add up to a singular experience that carries the audience on an emotional journey. I like what the current Wikipedia entry has to say about the architectural innovation known as the arch:

An arch requires all of its elements to hold it together, raising the question of how an arch is constructed.

Writers, too, know this feeling.

Of course, the answer in arch-building is to use a wooden frame, or a centring. You build the frame, and lay the stones over it. When you remove the frame, the stones remain in place. The shape of the frame defines the shape of the arch, but the frame itself is discarded, an now-useless artifact of the arch-building process. The arch, however, is more beautiful for the precision of the frame—and appears to hold itself together impossibly, an intoxicating combination of monumental might and graceful weightlessness.

Can you tell how I feel about outlining my writing?

Marked for The Law

I hope this exploration of Fountain’s outlining features sparks some ideas for how you might begin putting Fountain to use. And I hope it’s clear that neither I nor Fountain are trying to prescribe any particular workflow or writing style. Quite the contrary—Fountian is designed to be flexible enough to support any screenwriter’s habits.

Marked is available for OS X on the App Store. Download links and installation instructions for Screenplain can be found on Jonathan Poritsky’s blog.