log is the new lin

Saturday, May 14, 2005 at 6:57PM

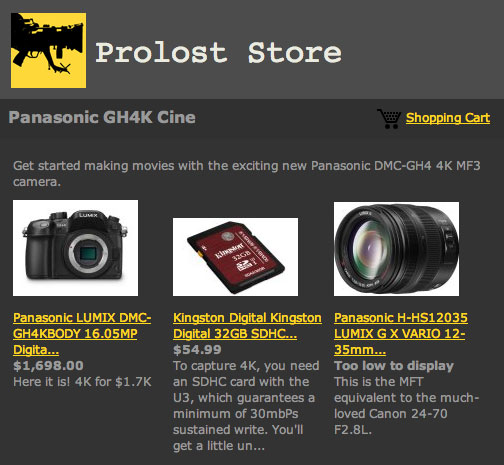

Saturday, May 14, 2005 at 6:57PM This the the Kodak DLAD image (Marcie) in log space, right?

This is the same image, linearized. Right?

Wrong, on both counts.

There are many misconceptions about Cineon files and the color spaces known colloquially as log and linear. The first is that Cineon files are stored in a log color space. It’s not that this is entirely false, it’s just that it’s not that simple. The pixel values in a Cineon file are represent dye densities on color negative film, and the relationships of these density measurements from one step to the next on the 10-bit scale are the same.

So while we say all the time that the Marcie Cineon file is “log,” what we really mean is that it is in Kodak's Cineon 10-bit encoding of negative densities as seen by the print stock. OK, so maybe I was being over dramatic when I said you were wrong earlier. That’s cool—let’s keep using the term log to describe Cineons, since the densities themselves are in fact logarithmic.

The problem is really with the second image. Many people freely use the term linear to describe images that look correct on their ≈g2.2 monitors. It’s particularly easy to fall into this trap when you are invited by your software to perform a “Log to Linear” conversion on a Cineon file. The standard practice is to use a Cineon conversion gamma equivalent to your monitor gamma and describe the results as linearized. But in truth, the results are gamma-encoded, as any image must be to look correct on a ≈g2.2 display, and are therefor not linear in the least.

As you can see here, a log curve and the gamma 2.2 curve are actually very similar. Gamma 2.2 images (which likely comprise the vast majority of digital images) actually bear more in common with log images than with linear ones. Logarithmic encoding and gamma encoding are both methods of distributing values perceptually, allowing them to be stored at reduced bit depths and to look correct on non-linear displays.

So it would be better to say that we converted the “log” Marcie above to “another kind of log-ish space” than to say that we made her linear. The eLin/ProLost/brave new future term wold be not log, not lin, but vid (like we talked about here).

“But Marcie looks all washed out in the log image and not in the second one (that I still desperately want to call linear).”

OK, I knew you were going to say that. Check this out. Here’s the log Marcie with all the values below 95 and above 685 clipped. Other than that, no color space change:

She's still “log” — all we've done is perform the clipping that happens in a standard Cineon conversion. Looks pretty darn similar to the second image at the top of the article, right?

So log Marcie is more like vid Marcie than linear Marcie. Linear Marcie is too dark to look at, but is the best Marcie for doing image processing operations on. Raw Cineon files look washed out because they contain so much headroom, not because they're log.

So repeat after me: Log is kinda like vid, and vid is not linear!