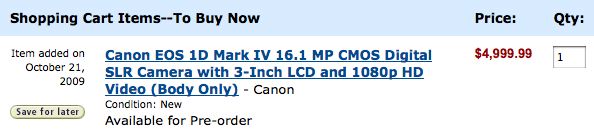

10 frames of a 7D resolution chart, shown here cropped 1:1, courtesy of Paul Lundahl of eMotion Studios (click the image to visit)

10 frames of a 7D resolution chart, shown here cropped 1:1, courtesy of Paul Lundahl of eMotion Studios (click the image to visit)

This article over at DVXuser caused quite a stir. Which is strange to me, because I’ve been telling you about this problem for a while now. Apparently a detailed, well-researched article with great visuals and clear explanations is more convincing than pithy quips and offhanded remarks. I’ll have to remember that.

The article by Barry Green is about the oft-reported “aliasing” artifacts in video from the Canon HDSLRs (5D Mark II, 7D, 1D Mark IV). Barry does a great job of backing up a few steps and defining the term aliasing.

Aliasing occurs when you observe, or sample, something infrequently enough that you create an impression of something that wasn’t there. Imagine a blinking light in a room with a door. You must open the door to check the status of the light. If you open the door often enough, you get a pretty good picture of the status of the light, maybe something like on, on on, off off off, on on on, etc. Your samples are frequent enough to accurately represent the light’s activity.

But imagine that you just happen to relax your light-checking to a frequency at which you see nothing but on. The light flashes once per second and you check on it once per second. As far as you know, the light is always on. Your infrequent samples give you a completely bogus picture of what the light is doing.

That’s temporal aliasing, because the insufficient sampling takes place over time. The classic cinematic example of this is the wagon wheel that seems to spin in reverse. Aliasing can also happen in spatial samples. For example, if you looked through venetian blinds at a zebra standing on his head, your partial sampling might reveal a white horse, or a black horse, depending on how the stripes lined up with the blinds.

So what does this have to do with Canon HDSLRs? The same thing it has to do with every digital camera. Every camera that uses photosites to create pixels has to deal with this venetian blind problem. There’s space between those photosites, and in that space you can miss out on important information about what was happening in front of the lens.

This is nothing new. We’ve long known that we shouldn’t wear detailed patterns or fine horizontal stripes when appearing on video. This despite the camera manufacturers’ inclusion of an Optical Low Pass Filter (OLPF), a very fancy term for a simple layer of diffusion atop the sensor designed to scatter the light a bit, so that the zebra stripe that might have slipped through the cracks will actually be spread to the pixels on either side of said crack. OLPFs work, but if they work too well the camera gets dinged by pixel-peepers as being too soft, so every camera company makes a judgment call about how much sharpness they’re willing to give up for less sizzling when a zebra does a headstand in a field of blowing grass.

The current crop of HDSLRs cheat in a big way to make video. Their sensors are not designed to blast an entire, full-resolution image out every 30th of a second. So Canon’s engineers (and Nikon’s and even Panasonics to some degree according to Barry) did what stills camera makers have always done with the “good enough” video modes on point-and-shoot cameras; they grab something less than every photosite. They look at the blinking light less often, and as a result they can pull off a whole picture at a rate speedy enough to make video.

But this picture is full of holes. And while the OLPF was designed to spread light between adjacent pixels, we’ve now dropped entire rows of pixels, so suddenly it’s insufficient by a huge margin.

What’s great about Barry’s article is that he shows you how this problem manifests itself on test charts (you know how I feel about those) and in practical use. But what’s even more shocking is that he reveals the actual resolution of these cameras. Thanks to the aliasing, it’s shockingly low. Yet the images appear crisp — and that’s Barry’s most artfully elucidated point: It’s precisely this infernal aliasing that makes the images seem sharp. If you fitted a 7D with an aggressive enough OLPF, the aliasing would disappear — along with any illusion that the 7D is a “full HD” video camera.

Some aliasing makes zebras appear stripeless. Some makes wagon wheels seem to spin in reverse. And some makes low-resolution images appear sharper than they really are.

So every HDSLR user needs to be aware of this and make a decision: Is that OK? Is the “fake detail,” as Barry repeatedly calls it, good enough for you?

For many, the answer is yes. As I have pointed out, the sex appeal of filmic DOF often wins out over technical shortcomings in shooters’ hearts, if not their minds.

Still, I have tried to warn you. I tweeted not long before Barry’s article that anyone pointing a 5D or 7D at a resolution chart is in for a nasty surprise. I also made mention of the Canon SLR’s low resolution in this post, which confused commenters, who responded that 1920x1080 was plenty. Of course it would be, but I was referring to the actual resolving power of the poorly-sampled images, which is much, much lower, as Barry empirically shows.

I even blogged this, over a year ago:

Let’s get something straight. The video from the Nikon D90 and the Canon 5D MkII is not of good quality. It’s over compressed, over-processed, over-sharpened, and lacks professional control. It skews and shears and shuts off in the middle of a take. It sucks.

I was really trying to warn you guys about this.

But you didn’t listen. It took Barry’s awesome article to drive the point home. Maybe it was his facts and figures. Maybe it was his patient explanations. Or maybe it was because he did not end his article with anything like what I usually say after decrying the downsides of these cameras. Stuff like:

What the D90 and 5D2 have done is show us that it’s no longer OK for video camera manufacturers, whether they be Sony or Canon or RED, to make a video camera that doesn’t excite us emotionally. Buttons and features and resolution charts just had their ass handed to them by sex appeal.

That Barry didn’t wrap up with something gushy like that led many readers to accuse him of anti HDSLR-bias, but I think those people are wrong. Barry is a 7D owner, and challenged one aspiring HDSLR-hater with this comment:

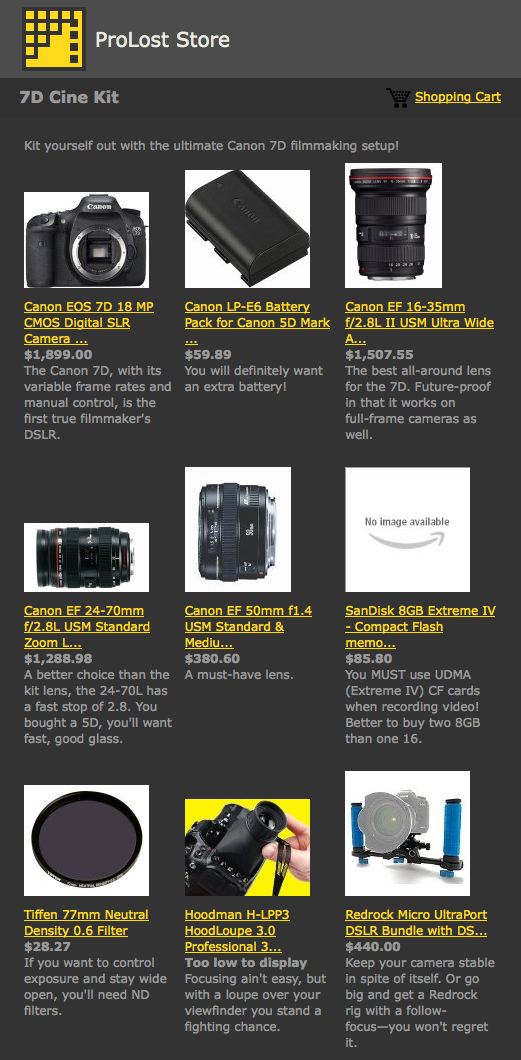

I’ve shot some (what I consider) really, really good looking stuff on a 7D. It’s capable of great results. And I’ve shot some trash on it too, and found it very frustrating for anything wide/deep focus. But it’s $1700! You’ve got to cut it a lot of slack for that!

All I’m doing is pointing out exactly how these things work. It’s up to you to decide whether your scenarios would work within their limitations. If you’re shooting faces, they can excel. The more that you can keep out of focus, the better they’ll do. The more that’s in sharp focus, the more potential for negative complications from aliasing.

They are not a magic bullet. They are not Red-killers. They’re not sharper than conventional video cameras. Keep that all in perspective, and use them for what they’re good for, and they can do astonishingly good things at an unprecedented low price point.

Nicely said Barry. All around.

For my part, I’ve focused on the positive aspects of the 5D Mark II and the 7D because I like where they are pushing things. But I do owe it to you guys to show you that I take this aliasing problem seriously. You need to understand it well to evaluate whether an HDSLR is right for you. And I would hate to give Canon the impression that we’re content with looking at the world through venetian blinds.

Tuesday, December 29, 2009 at 4:36PM

Tuesday, December 29, 2009 at 4:36PM