Some people procrastinate writing by shopping for notebooks, or perfecting their Markdown preview CSS. Some procrastinate their work by cleaning their desk, and some procrastinate cleaning their desk by working.

I procrastinate storyboarding a new video I’m working on by creating iPad templates and After Effects presets designed to make storyboarding easier.

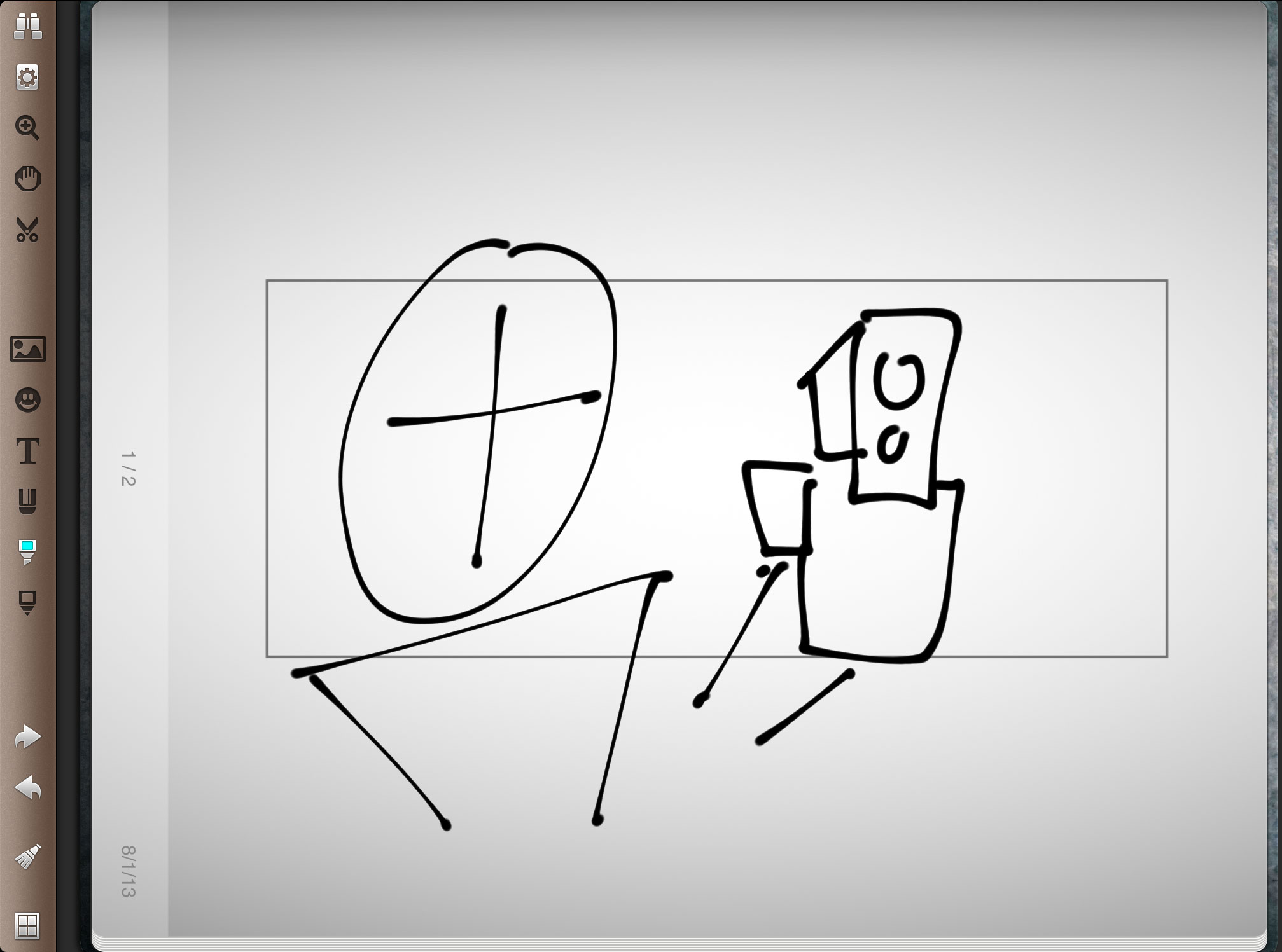

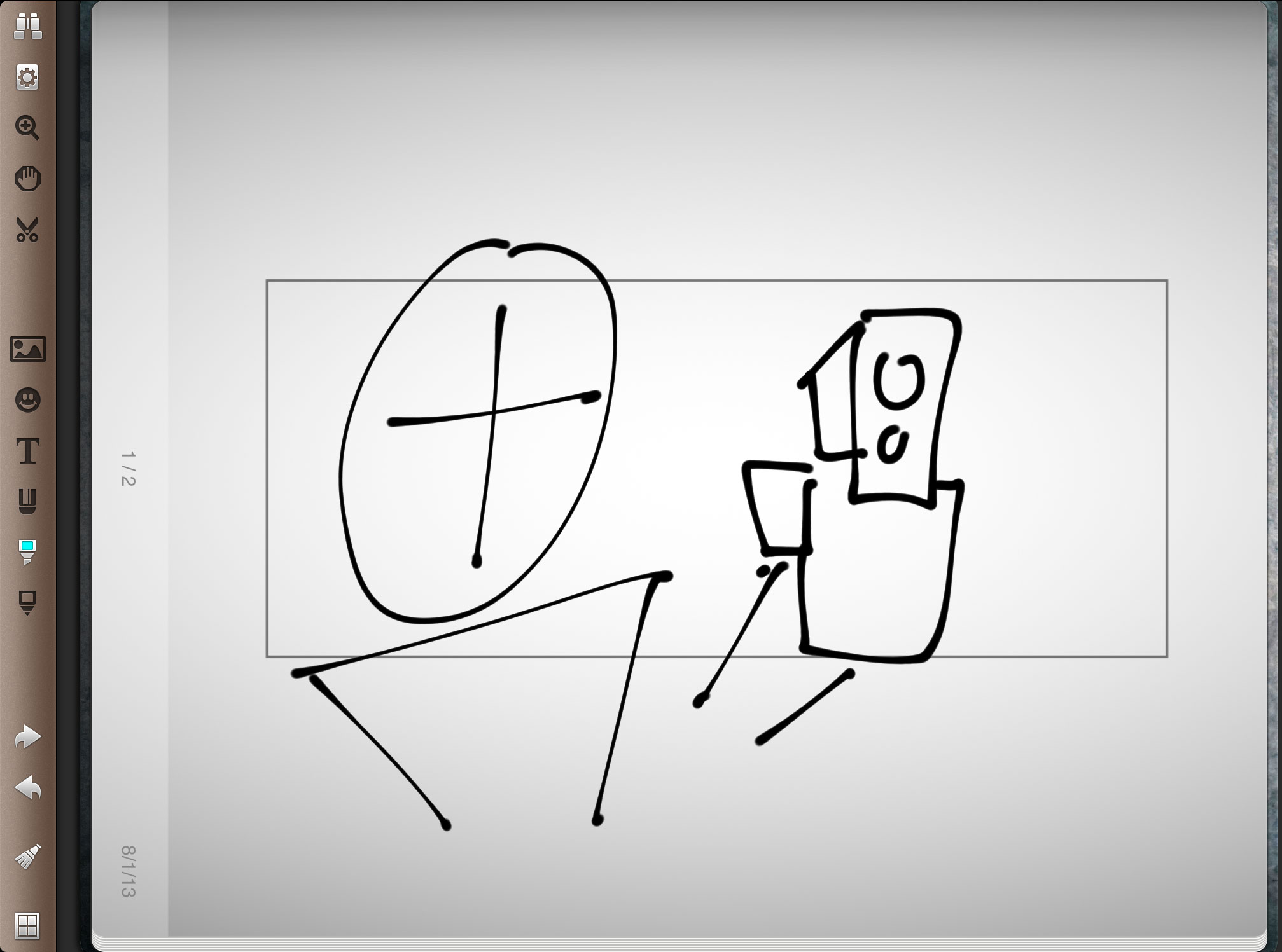

If you read my post on storyboarding on the iPad, you may remember that my app of choice was Penultimate. I lovingly created storyboard templates for it and defended its clean simplicity. Penultimate makes it easy to sketch out, edit, and rearrange a series of boards using a custom template, and export the results to a PDF.

There was one feature that I wished for however: the option to export to individual, numbered PNG files. If all you want to do with a storyboard is print or share it, a PDF is perfect. But if you want to take the frames and create something else with them, it’s much better to have them as individual files.

For example, you might want to bring them into Storyboard Composer HD, where, right on your iPad, you can sequence them into a timed-out animatic, or board-o-matic. complete with camera moves and sound.

Or you may want to edit this board-o-matic on your computer. Usually I use NLE software such as Adobe Premiere for this kind of thing, but the power this solution offers comes with a price: doing some things is less simple than in a dedicated app such as Storyboard Composer.

It occurred to me that I could use After Effects to automate some of the most common board-o-matic tasks. Although After Effects is not a great environment for creative editorial, it is an excellent platform for automating some kinds of motion and imaging tasks.

But first I needed to solve my problem of getting individual PNG files of my storyboards. I began investigating tools for ripping images out of PDFs, and simultaneously I continued my gentle harassment of Penultimate’s creator, Ben Zotto. The app allows a single page to be exported as a PNG, so, I reasoned, there’s a certain consistency in offering this option for multi-page exports.

You may recall that Ben and I blogged back and forth about how users should best make feature requests of developers. It was a bit of a love-fest, and I deeply admired Ben’s commitment to a simple, clean, user experience.

In May of 2012, Penultimate was acquired by Evernote, and is now free. It’s still great, but I’m no longer using Penultimate for storyboarding on the iPad.

A Little Less Less

Back when I first posted about storyboarding, many readers suggested alternatives to Penultimate. There is no shortage of busy, complex, feature-crowded notebook apps in the App Store. Most of the suggested apps made my head hurt with their cluttered UIs. But a few folks suggested that I look at Noteshelf ($5.99 on the App Store).

It’s hard to imagine that Noteshelf didn’t draw inspiration from Penultimate in its design and feature set. It’s a note-taking and drawing app that works on the model of multi-page notebooks that can be lined with various virtual “papers,” including ones you create yourself.

Most importantly for my storyboarding workflow: your drawings can be exported with, or—crucially, without, the paper template embedded, in various formats, to various destinations, including numbered PNG files to Dropbox.

But Noteshelf is not just a me-too app. It’s sturdy, attractive, well thought-out, and not without restraint. And there are a few things about it that I like better than Penultimate. Its “ink” overlaps more realistically. It features highlighter “markers” that are great for shading storyboards. And it works much better in landscape orientation.

Templates

Like Penultimate, Noteshelf allows you to create custom paper templates. But instead of helpfully packaging them up in a unique file type that can be one-tap installed like Penultimate, Noteshelf simply offers the option to import any image from your iPad’s Photo Library.

Quirks aside, Noteshelf offers almost everything I want from an iPad storyboarding sketchbook, and few things I don’t. I can quickly bang out a bunch of questionably-legible cinematic chicken-scratches and export them to my laptop. So what do I do with them then?

Prolost Boardo for After Effects

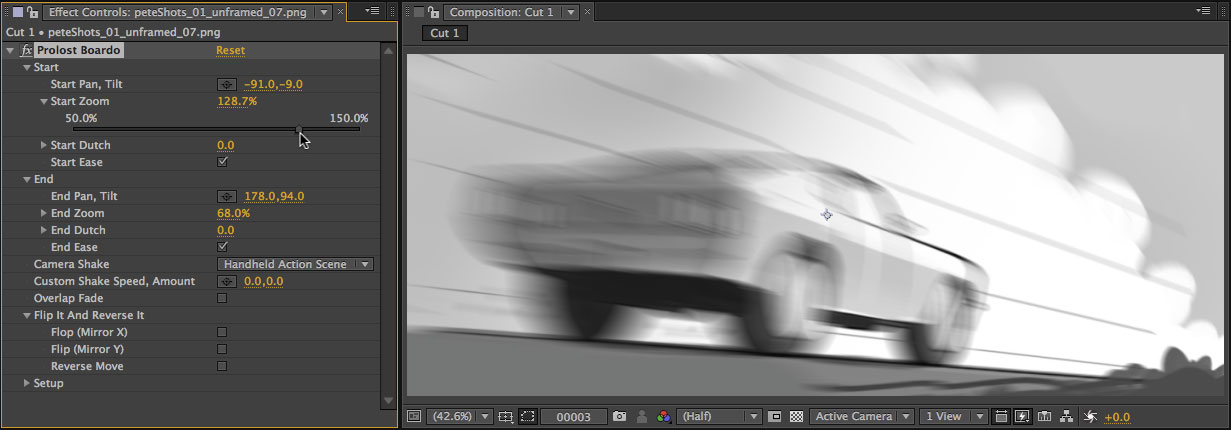

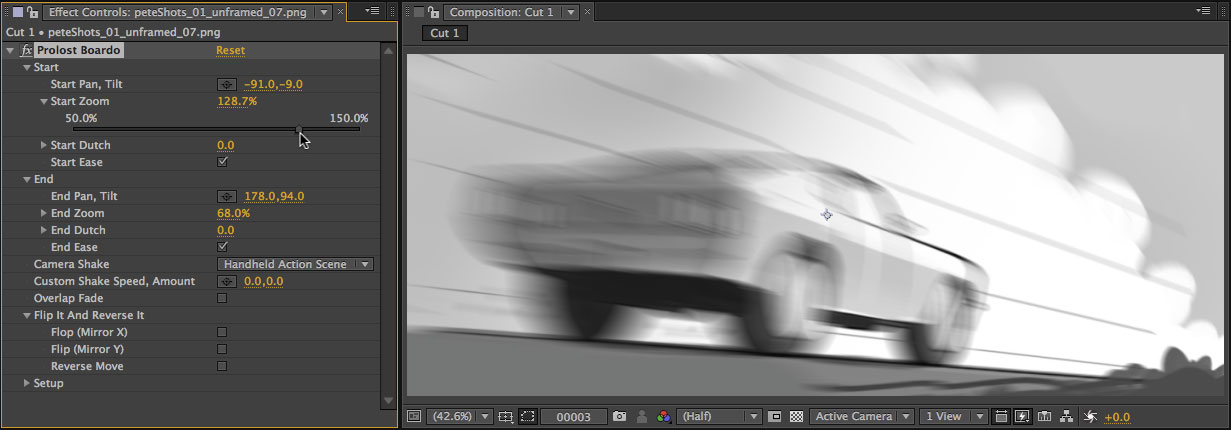

Prolost Boardo is a set of three Animation Presets for Adobe After Effects that automate the process of creating an animated storyboard, or board-o-matic.

Easily create animated camera moves, including cross-dissolves, camera shake, and cycling animations, all without using any keyframes.

The video shows you how it works, but it’s deceptively simple. There’s some complex math going on under the hood to make these virtual camera moves smooth, realistic, and predictable. Anyone who’s ever tried to animate 2D artwork in an NLE can tell you how frustrating it can be.

Boardo, on the other hand, makes it so easy that you might use it just for fun.

Boardo works with any kind of storyboards, wherever you create them (and includes instructions on customizing the settings for whatever format you like), but it defaults to work with frames drawn in Noteshelf using one of two templates. You can download them here.

This is is the most powerful and complex tool I’ve created for the Prolost Store, and I really think you’re going to like it. Prolost Boardo is available now for $24.99.

Monday, October 14, 2013 at 9:32AM

Monday, October 14, 2013 at 9:32AM  Stu

Stu