What I Do With My iPad Part 1: Storyboarding

Wednesday, June 15, 2011 at 9:32AM

Wednesday, June 15, 2011 at 9:32AM There’s an iPad stylus review buried in here. But first, some background on why I’m so excited to be storyboarding on a tablet.

As I detailed in The DV Rebel’s Guide, storyboards don’t have to be immaculately drawn to be effective. Which is lucky for me, because I have let wither whatever drawing ability I once had. To me, the boarding process is about flow. I need a tool that allows me to bang out my ideas as they come. For as long as I can remember, that’s been printed storyboard templates and a mechanical pencil. That’s how I whip up my “thumbnail boards,” which are usually stick figures, arrows, and incomprehensible squiggles.

This process is then followed by a rather ugly chore of scanning, cleaning up, and cropping in Photoshop.

To speed the process and avoid the manual labor, I’ve tried using various storyboarding systems and software, including ClipSketch and Storyboards on the iPad and SketchUp on my laptop, but I always come back to the simple, expressive basics of hand-drawn boards. They may be simple, but they’re my simple, and the camera angles I draw are never limited by what clip art I had on hand.

In the early days of the iPad, one of the first apps I bought was Penultimate by Cocoa Box Design. Penultimate was designed to be your digital Moleskine notebook, a simple and elegant blank page on which to doodle, sketch, or write. Whether it was the elegance of the app or the fluidity of the pseudo-pressure-sensitive drawing, Penultimate earned a permanent place on the front screen of my iPad.

I approached the developer, Ben Zotto, about my desire to use Penultimate for storyboarding. The app then offered a selection of three paper styles; plain, lined, and graph. Rather than myopically suggesting he add storyboarding templates, a rather niche use case, I suggested that it might be of general interest to his users to allow custom papers. I must not have been the only one thinking this, because just this May, Ben released Penultimate 3.0 with exactly that feature. He even used a film storyboard as his example.

Why is Penultimate, a simple, general-purpose notebook app, the best iPad storyboarding tool? Turns out there’s a critical mass of features that add up to awesome:

- Custom templates (papers)

- Delete, re-order, and duplicate pages in a lovely thumbnail view

- The best “feel” of any iPad drawing app (especially with a stylus, see below)

- Just the right number of ink colors (almost, see below)

- Easy PDF export of all or just some of your pages

The DV Rebel often repurposes tools from other disciplines. Penultimate is a great example of filmmaking software that isn’t just for filmmaking. I’m so fired up about my new storyboarding workflow that I’m sharing my Prolost storyboarding templates.

There are templates for HD aspect ratio and ‘scope, portrait and landscape. The landscape ones come in variations featuring a rule-of-thirds grid and a “blackout” look. Tap these links on your iPad and they’ll open in Penultimate.

Some tips:

- You can change papers anytime as you’re working. So, for example, you could switch the thirds grid on and off as needed.

- Most of the HD templates have a corresponding layout in the ‘scope aspect, so you can see how your shots will look framed for either format by switching papers.

- You can choose whether the paper pattern is exported with the drawings or not.

- You can choose which pages get exported when saving/sharing a PDF.

- Landscape mode is not as slick as it should be when re-ordering pages or exporting. On the Mac, you can use Preview to rotate your pages to the correct orientation and re-save the PDF.

- To make your own template, make a black-on-white PNG file at 718 by 865 pixels, and save it to your iPad’s Photo Library. You can then import it in the Papers popover menu.

Aside from better landscape support, what’s missing from Penultimate? Not much. The app allows single frames to be saved and shared as JPEGs, but only allows multi-page export as PDF. For my workflow, I’d occasionally like to export a series of JPEGs. I’d also like just one more pen color: a barely-there gray for roughing-in a drawing before refining it in black or dark gray.

The Boxwave Capacitive Stylus and the Wacom Bamboo Stylus for iPad

The Boxwave Capacitive Stylus and the Wacom Bamboo Stylus for iPad

If you’re going to be drawing on your iPad, you’re going to want a stylus. I’ve owned three, the PogoSketch, the BoxWave, and Wacom’s Bamboo Stylus for iPad.

The Pogo Sketch is affordable enough to buy just to decide if you like using a stylus with your iPad. It’s also available at most Apple retail stores, although you’ll have to ask for it — it’s not on display.

The BoxWave is almost as affordable as the Pogo, but I found it to be much better. It’s small, as these things seem pathologically intent on being, and light. But the rubber tip gives a great drawing feel on the iPad screen, and it features a clever tether with a plastic plug at the end that fits in your tablet’s headphone jack, which improves your chances of actually having the dang thing with you when inspiration strikes.

Wacom makes the wonderful and not inexpensive tablets and Cintiq pen displays, so leave it to them to come out with a premium capacitive stylus. Their Bamboo Stylus for iPad is the most expensive one I considered. It’s got a nice heft, it’s long enough for grown-ups, and it has the finest tip I’ve seen on an iPad stylus — which may or may not mean anything tangible, but it just seems to feel better in use.

Expensive things are expensive. But to me, a $10 stylus that I never use is more expensive than a $30 that I love and use often. The Bamboo is by far my favorite and worth every penny it cost, and every day I waited for it to arrive.

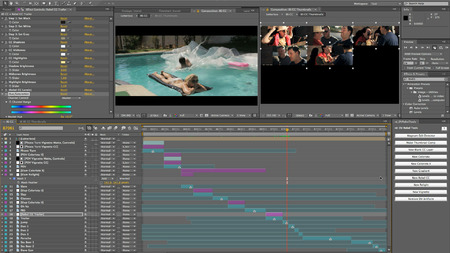

What do you do with all these drawings once they’re done? You might consider dropping them into Storyboard Composer (UPDATE: Now available for iPad as Storyboard Composer HD) or build an interactive presentation of them in Keynote or the excellent Portfolio (all of which would be much easier with multi-page JPEG output). You might bring them into After Effects or your favorite NLE to cut them into an animatic. Our you might just work with them as a PDF or a printout. Whatever you do, I think you’ll find that drawing storyboards on your iPad is finally ready to replace paper and pencil.

See also: What I Do With My iPad Part 2: Write With a Keyboard

Stu

Stu

A lot has changed since this post! Penultimate was acquired by Evernote, and I’ve switched to Noteshelf for my storyboards—and built a cool tool for animating them autimatically, called Boardo.

Stu

Stu