Kindles are now cheap.

Many people predicted that there would be a major upset in the publishing world when the Kindle dropped below $99. They were wrong—it happened well before that.

Independent authors have been able to self-publish their work on or through Amazon for quite a while, but in the last year or so there has been an explosion of success stories. Authors like John Locke, Amanda Hocking, Andrew Mayne, and Joe Konrath have appeared on best-seller lists right alongside authors whose names are a part of any trip through an airport concourse.

The Collision

The reason for this, as I see it, is a collision of several factors:

- The popularity of the Kindle. Even when it was expensive and clunky, the Kindle was a hit. Now it’s cheap and even pretty. And it’s not just a device—it’s a free app for a device you already own.

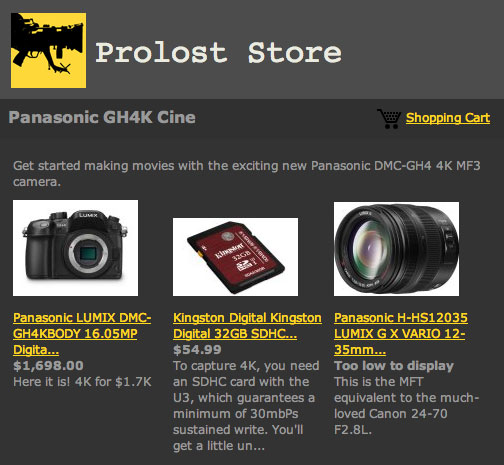

- Amazon’s Kindle Store. Amazon recognized a seemingly obvious fact: A Kindle owner doesn’t want to shop for books, pick one they like, and then find out if it’s available for Kindle. They want to shop for Kindle books. The consequence is that self-published ebooks appear right alongside electronic versions of traditionally-published books, with no stigmatizing differentiation.

- Reviews. Amazon’s reviews are generally pretty good by internet standards. Amazon book reviews seem even better on average. But reviews of indie books are plentiful and passionate. A True Fan of a self-published author is going to write a much more compelling review than a book-of-the-month casual reader—and be much more likely to take the time to do so.

- The reason for this is that successful indie authors are engaged with their audiences in a way that few traditional authors are. They have no other choice, since they are their own marketing departments. The result is that readers of indie fiction feel a close kinship to their favorite authors. They recommend them to friends, eagerly write heartfelt reviews, and buy without a second thought.

-

And of course, price. Many indie novels are as inexpensive as 99¢. As self-published author John Locke said in his book How I Sold 1 Million eBooks in 5 Months!:

…when famous authors are forced to sell their books for $9.95, and I can sell mine for 99 cents, I no longer have to prove my books are as good as theirs. [They] have to prove their books are ten times better than mine!

The 99¢ price point is particularly interesting, and has, of course, been the subject of much hand-wringing. Amazon has a fixed royalties model for ebooks: For titles priced between $2.99 and $9.99, publishers take home 70%. Any other price nets 35%. For every book an indie author sells at 99¢, they receive 35¢. For a $2.99 book, a self-published author sees a royalty of $2.00. Again, Locke has an emphatic point of view as to why he chooses 99¢:

My decision came down to whether I thought I could sell seven times as many books at 99 cents as I could at $2.99.

By my calculations he only has to sell six times as many books to beat the $2.99 model ($0.35 x 7 = $2.10). There’s much more to Locke’s position on this though, so I recommend you read his book if you’re genuinely interested.

Some decry the buck-a-book pricing as devaluing literature and destroying humanity. What it’s meant for me in practice is that I’ve discovered some fun new authors, and that the “gateway drug” principal is real. Cheap books got me reading more, and now I buy regular-priced ebooks more frequently than I’d ever bought dead-tree fiction.

I’m not the only one. Amazon’s Kindle best-sellers page has been a mix of indie offerings and traditional titles for as long as I’ve been aware of it. Books there range from New York Times best-sellers to pulpy self-published impulse buys, at prices ranging from $12.99 to free. Indie publishing has arrived.

The Opportunity

I write a lot here about accessibility of storytelling tools. Cameras keep getting better and cheaper. Post tools once reserved for the stratospheric high-end trickle down to our laptops. But there is no more democratized form of expression than the written word. If there’s a story in you, write it down.

That’s been true forever, but now you can take a small additional step and share your story with the world. Maybe you’ll give it away. Maybe you’ll sell a million copies.

I’m writing this now because National Novel Writing Month (or NaNoWriMo) is about to begin. If you’ve ever had the itch write a book, you can do so virtually surrounded by a supportive internet community of writers who gather once a year to bang out a draft in 30 days. It’s a wonderful way to practice the best writing advice there is: Don’t get it right, get it written.

NaNoWriMo considers a novel to be 50,000 words or more. To get there in 30 days, you’d need to write 1600 words per day—fewer than in this blog post. It’s not easy, but it can be done. More importantly, failing at something like that is a lot better at succeeding at the dumb crap you were planning on doing in November.

But I’m a Filmmaker

This is the bit I’m still working out. So it’s obviously the most interesting part.

As wonderfully detailed on the excellent Scriptnotes podcast by screenwriter and master blogger John August, when you sell a script, you enter into a somewhat fictitious work-for-hire agreement. Your script and its copyright become the property of the purchaser. Even though it was your idea, you agree to pretend that the studio hired you to write it. There are several very good reasons for this structure that John and his co-host Craig Mazin explain perfectly, but one downside is that you maintain no ancillary rights to your work, You can sell a script and never see another dime beyond the sale price.

This is not true of novels. You’ll hear stories about producers developing projects as graphic novels first before pitching them as movies. Part of the reason is so that a studio can see pretty pictures of what their movie might look like, but another big part is that the copyright holder of the comic will maintain the literary rights to the story. This means royalties on any film that gets made based on that work, including any sequels, TV series, or stage production—royalties that would not likely be a part of a spec script deal.

On top of that, Hollywood is currently beyond reluctant to invest in any idea that doesn’t have built-in familiarity with an audience. It’s potentially easier to get Scott Pilgrim vs. the World made than Inception, even though Scott Pilgrim was a niche comic with tiny circulation, and Inception was the pet project of a can’t-lose filmmaker, with a huge star attached.

As a filmmaker, you might have an easier time pitching a movie based on your “breakout hit” (hundreds sold!) or even “cult classic” (dozens sold!) self-published novel than you would with an original spec screenplay. And if your pitch is successful, the “back end,” as Hollywood folks like to say, could look much better for you, depending on the deal you negotiate.

Nerd Your Way To 50K

If you decide to accept the NaNoWriMo challenge, I have one and only one recommendation for you: Get Scrivener. Last time I pimped Scrivener to you, it was version 1.0, Mac-only, and had only fledgeling screenwriting features, which comprised my primary interest in it. Scrivener 2.0 offers many improvements to the screenwriting features, but helping you write long-form fiction is what this beast was truly created to do, and at that it excels.

There’s so much to say about Scrivener that it deserves a whole post (maybe more), but my most recent love affair is with its Dropbox syncing feature. To get a taste of it, go here and scroll down to Folder Syncing. Combine this feature with one of the many Dropbox-enabled mobile text editing applications such as Elements or WriteUp and you’ll never be more than a few taps away from tweaking your prose.

Scrivener also offers detailed options for exporting .epub and .mobi files, the book formats for Apple’s iBooks and Amazon Kindle, respectively.

Sure, if you’re a great writer, you don’t need anything special (services such as Smashwords will create an ebook for you from a properly formatted Word file). But if you’re a terrible writer like me, you need all the help you can get. Scrivener is a lifesaver. Check it out for Mac and Windows.

Read. Write.

Writers read and readers write. As Merlin Mann wrote recently regarding the lovely new Instapaper 4.0, the mere decision to read more can make your life better. I look at the purchase of a Kindle as an active step into an exciting new world of democratized storytelling that starts with the written word but that ripples out as far as blockbuster movies. Get reading. Maybe even get writing. You’re a part of something important.

Update on Thursday, October 20, 2011 at 5:29PM by

Stu

Stu

Amazon just announced Kindle Format 8, which offers several fancy new features such as embedded fonts, fixed layouts, high resolution graphics, and “panel views” for graphic novels.

[via Andrew Mayne]

Monday, February 25, 2013 at 3:40PM

Monday, February 25, 2013 at 3:40PM