Red Epic HDRx in Action

Thursday, March 17, 2011 at 7:37PM

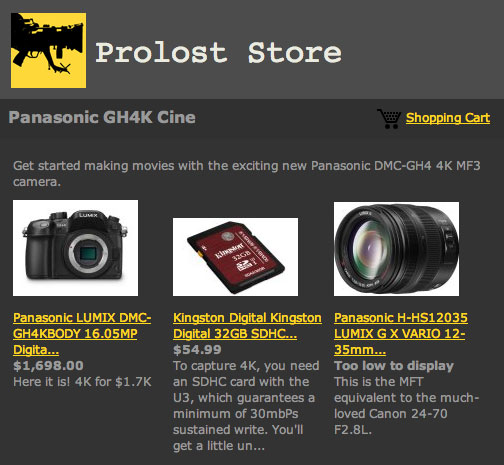

Thursday, March 17, 2011 at 7:37PM RED came out of the gate strong with a message of the importance of spatial resolution. We werre told that the RED One was an important camera because it “shot 4K,” and 4K is better. A more-is-more argument that I agree with only in part.

In the stills world, the obsession with resolution became the “megapixel race,” and only in the last couple of years has some sanity been brought to that conversation. Canon’s 14.7 megapixel PowerShot G10 was assailed for being a victim of too much superfluous resolution at the expense of the kind of performance that really matters, and Canon backpedaled, succeeding it with the G11 at 10 megapixels.

Why is more not always more? First, there’s the simple matter that there is such a thing as “enough” resolution, although folks are happy to debate just how much that is. But there’s also an issue of physics. Only so much light hits a sensor. If you dice up the surface into smaller receptors, each one gets less light. Higher-resolution sensors have to work harder to make an image because each pixel gets less light. This is why mega megapixels is a particularly disastrous conceit in tiny cameras, and why the original Canon 5D, with it’s full-frame sensor at a modest 12.8 megapixels, made such sumptuous images.

All things being equal, resolution comes at the expense of light sensitivity. Light sensitivity is crucial for achieving the thing most lacking in digital imaging: latitude.

What we lament most about shooting on digital formats is how quickly and harshly they blow out. Film, glorious film, will keep trying to accumulate more and more negative density the more photons you pound into it. This creates a gradual, soft rolloff into highlights that film people call the shoulder. It’s the top of that famous s-curve. You know, the one that film has, and digital don’t.

You know how sometimes you drag a story out when you know you have a good punchline?

When RED started talking about successors to their first camera, it was all about resolution. Who ever said 4K was good enough? We need 5K and beyond! Of course the Epic would be have more resolution. But would it have more latitude?

As the stills world’s megapixel race became the high-ISO race (now that’s something worth fighting for!), so too did the digital cinema world get a dose of sanity in the form of cameras celebrating increased latitude. Arri’s Alexa championed its highlight handling. And RED started swapping its new MX sensor into RED One bodies, touting its improved low-light performance and commensurate highlight handling.

Life was good.

And then Jim Jannard started hinting at some kind of HDR mode for the Epic. HDR, as in High Dynamic Range, as in more latitude.

The first footage they posted seemed to hint at a segmented exposure technique. It looked like the Epic was using two frames two build each final frame, and Jim later corroborated this. The hero exposure, or A Track, would be exposed as normal (let’s just say 1/48 second for 24p at 180º shutter). The X Track would be exposed immediately afterward beforehand (see update below) at a shorter shutter interval. Just how much shorter would determine how many stops of additional latitude you’d gain. So if you want four additional stops, the X track interval would be four stops shorter than 1/48, or 1/768 (11.25º).

The A Track and the X Track are recorded as individual, complete media files (.R3D), so you burn through media twice as fast, and cut your overcrank ability in half. Reasonable enough.

But could this actually work? You’d be merging two different shutter intervals. Two different moments in time (again, see comments). Would there be motion artifacting? Would your eye accept highlights with weird motion blur, or vise versa? Would the cumulative shutter interval (say, 180º plus 11.25º) add up to the dreaded “long shutter look” that strips digital cinema of all cinematicality?

RED’s examples looked amazing. But when the guys at fxguide and fxphd got their hands on an Epic, they decided to put it to the real test. The messy test. The spinning helicopter blades, bumpy roads, hanging upside down by wires test. In New Zealand. For some reason.

Thankfully, they invited me along to help.

But before I’d even landed in Middle Earth, Mike Seymour had teamed up with Jason Wingrove and Tom Gleeson to shoot a little test of HDRx. They called it, just for laughs, The Impossible Shot.

This is not what HDRx was designed to do. It was designed to make highlights nicer. To take one last “curse” off digital cinema acquisition. This is not that. This is “stunt HDRx.”

And it works. Perfectly.

Sure, dig in, get picky. Notice the sharper shutter on the latter half of the shot. Notice the dip in contrast during the transition. The lit signs flickering.

Then notice that there’s not another camera on the planet today that could make this shot.

I guess Mike should really have called it “The Formerly Impossible Shot.”

Read more at fxguide, and stay tuned to fxphd for details on their new courses, coming April 1.

Stu

Stu

Graeme Natrress confirmed for me that the X track is not sampled out of the A Track interval, but is in fact a seperate, additional exposure. There is no gap between the X and A exposures, but they don’t overlap.

The just-posted first draft of the Red Epic Operation Guide has a few nice deatils about HDRx as well.

Reader Comments (12)

Very commendable that we now seem to have a camera which beats film. It has film's latitude, it has enough resolution to compete, it causes 35mm to die rather earlier than I expected.

How do we top this?

You mention that there is such a thing as too much resolution, but I think there is such a thing as too much dynamic range as well.

Let's face it HDR taken to extremes just looks awful. Not here - that's a sensible use. But when you go past 20 stops you get a low contrast image, bizarre colour and an unnatural look like a 5 year old 3D engine used on Gears of War.

You can have too much latitude... EPIC has enough... so what is the next version going to improve on? Improved HDR - no. Improved res? No we have enough.

You can even have too much high ISO performance. What's the point with making darkness look like broad daylight?

Everything reaches it's limit eventually and plateaus.

"But when you go past 20 stops you get a low contrast image, bizarre colour and an unnatural look like a 5 year old 3D engine used on Gears of War"

like for example here, at around 2:00:

http://vimeo.com/16414140

so there are good and bad ways to use this tool, just like with most other ones

as for the plateau thing, I haven't upgraded my two main computers in the last 3 years, except for some little things like replacing dead HDDs and switching to an nvidia graphics card; apart from these minor things, I find they're good enough, and don't feel any urge to get a new one

I guess the same thing could happen to cameras in ten years, but we're definitely very far from that

for a start, there's the price issue: keep everything else just the same and lower your costs so you can sell the camera for half the price, and I'll call it a very significant breakthrough!! and there's a lot of headroom for these high-end cameras to go cheaper...

plus we'll surely find along the way something else we want our cameras to do

No no no, there is not something called "too much dynamic range", those ugly HDR's look ugly simply because someone tried to *squish* too much dynamic range into the black-and-white range. There is NOTHING wrong with having great incoming dynamic range, but still letting it blow to white (at some level) in the final output.

HDR's should be about highlight management and REASONABLE dynamic range squeezing, NOT about doing the COMPLETLY impossible - because then it looks like crap. This is an example of NOT looking like crap. Many things out there labelet "HDR", unfortunately, is of the "smashed together into insanity" variety, and I hate 'em all with a passion.

What worries me is that in a lot of the hdr research literature, people are fond of compressing stuff in the luminance domain, not R, G and B individually. The idea they have is to "retain saturation", but I think that looks bad. The photographic tonemapper in mental ray (which I wrote) intentionally does compression per-component, which causes the highly compressed stuff to push towards white, which it SHOULD (and does in film). Lots of those ugly "overprocessed" images comes from the artificial retention of saturation in what used to be "overbright".

I havn't seen enough HDRx footage to be able to judge if it does it right or not, but hey, this looks nice. :)

/Z

Hehe; it was worth the wait

Wicked shot Stu.

Just reading closely, I wanted to share this:

I believe the X frame is exposed first, within/during the full shutter, as an initial readout of the photosites without stopping the exposure. That's why the magic motion looks so great.. like a more filmic layered motion.

Maybe now that things are "plateauing" people will begin to focus once again on what's really important. Movies are storytelling. Storytelling with pictures, to be sure, yet storytelling as it has been since before the days of Homer, before the shanachies, before the griots, before Gilgamesh. The first recounter of the day's events around a smoldering cave-fire started this, and it is one of the oldest and finest human traditions.

The very best stuff I work on is in the service of moving a good story forward. Whatever that story might be, the tools are not the project, they are the means of the project.

And now we have better and better tools - close, perhaps, to some point of diminishing (onscreen) return as they continue to advance. Unless, of course, our eyes and ears evolve in some new ways.

(None of this is meant to slight the other uses of some amazing technology, making dramatic improvements in many other aspects of life - let those happen!)

Now, the challenge is on us to use those incredible new tools to do better what we have always done, not only to marvel at the additional things they might let us do.

This is so awesome! RED is really making serious waves here. However, I wonder if there could be a poor man's solution to this shot as well. Using 3D technology of combining multiple cameras, you could place two cameras on a 90-degree angled rig and have them completely synced: typically NOT what you'd want for 3D, but for doing HDR video it's the way to go.

Then, you could expose for one camera for the highlights and the other for the darker parts. By combining both simultaneously recorded images you could possibly achieve a similar result. Feel free to read my article on HDR Video: http://www.reelseo.com/exploring-hdr-video/ and check out some more HDR sample videos on Vimeo: http://www.vimeo.com/groups/hdrvideo

[Stu, I meant to post this comment here, not on the other article]

A technical correction to geek out on -- this is backward:

"The hero exposure, or A Track, would be exposed as normal (let’s just say 1/48 second for 24p at 180º shutter). Then the X Track would be exposed immediately afterward, at a shorter shutter interval. Just how much shorter would determine how many stops of additional latitude you’d gain."

The short exposure happens first. This reason for this is then the two exposure times can overlap, reducing the disparity between the images for easy HDR processing. This done by initializing the sensor for integration once, but doing two read-outs, without a reset between reads. The first read-out is at say 1/384th of a second (for 3 stops HDR) and the second at the normal 1/48th (or 7/384th later than the first read.)

- - - - time - - - ->

[reset][short exp.]

. . . . . [-- regular exposure --]

vs

- - - - time - - - ->

[reset][-- regular exposure --][reset][short exp.]

It is a pretty cool technique.

Thanks for the explanation and visuals David! I've updated the post to reference your excellent illustration.

If I was in high priced Hollywood lighting rentals.. I'd buy EPIC's and get out of that business.

Sigh. Lust lust lust lust lust. I'm going to have to visit the bank manager soon by the looks of it.

I've been having informative discussions on DVXuser about reliance on "fixing it in post" which to some people appears to include a mild grade to remove a slight warm colour cast and apply an S-shaped tone curve. Coming from a stills background this doesn't even begin to count as "fixing it", it is just a natural-as-breathing way of working if you have relatively shot-flat images. I am becoming increasingly convinced that for my own sanity I need to invest in something which holds up under the grade a lot better than dSLRs and the AF100... like a Red, it seems!

Fix it in post is no answer. But upping the data you store to allow more informed decisions to be made in the tranquility of the edit suite rather than in the pressure cooker on location just seems like common sense to me.

Cheers, Hywel

This is the best explanation of shoulder I've ever heard.. Awesome.