If you’re shopping for a DSLR right now, for the primary purpose of shooting video (being familiar with all the pros and cons), what you want is the Canon 60D.

I felt compelled to write this because the 60D seems to get left out of the conversation a lot, and it shouldn’t. It’s the best filmmaker’s DSLR out there right now. People still ask my which they should buy, the 5D Mark II or the 7D, and when I recommend the 60D, I sense resistance. How is it possible that a sub-$1,000 camera body shoots video as good as one costing $600 more?

The 7D is a great camera, and it was the first HDSLR to offer a smattering of useful frame rates and manual control. It also is a Canon, so if you were a 5D Mark II shooter, a 7D was an easy body to fold into your kit. I bought one the day they became available, and encouraged you to do the same — arguing then, as I still believe today, that the APS-C sensor size — while not as luxuriously huge as that of the 5D Mark II — is a perfect size for filmmaking, being a close match to the Super35mm film frame.

The sensors of the 7D and the 60D are the same size, but with the 7D you’re paying for a best-in-class APS-C stills camera, which you may or may not need. It has a more advance autofocus system than the 5D Mark II, a weatherproof metal body, and dual DIGIC 4 chipset for rapid-fire motodrive. If you’re not a serious stills shooter, these features are overkill. They have no affect at all on the camera’s video performance.

Still, the 7D got lodged in the hearts and minds of not only shooters, but their clients. Everyone knows the 7D.

Then along came the Rebel T2i and the 60D. Both have almost the exact same video features as the 7D (with one notable exception, as you’ll read in a moment). The 60D even has a handy feature that the 7D lacks: manual audio level control. But more importantly, the 60D alone has something I routinely wish my 7D had: an articulating LCD screen.

This single feature is enough reason to recommend the 60D. Quite simply, it’s painful and often impossible to shoot video with an HDSLR without an external monitor. While the amazing Zacuto Z-Finder is great for shoulder-mounted work, if you’re like me, you often shoot at something other than eye-level. A flip-out LCD has been on my HDSLR wishlist for a long time, and we finally have it with the 60D. And by the way, you can use the Z Finder with the 60D, as shown here.

I don’t have a 60D (yet) or a Rebel T2i, but everyone I’ve spoken with who has done comparisons says the video from the three cameras is nearly identical. So here’s my recommendation:

If you are just getting started and are on a budget, sure, consider the Rebel T2i. Do not, under any circumstances, buy it with the kit lens. A year ago the only SLR worth shooting video with was $2600. You just got one for $750. Take the extra money and buy some fast lenses. At the very least, get a thrifty fifty.

If you are a serious amateur or aspiring-pro photographer who doesn’t care about full-frame or “real” pro bodies like the 1D Mark IV, and you also want to shoot video, the 7D is a great camera. And it is worth noting that the 7D does have one advantage over the 60D: The 7D outputs an HD signal through its HDMI port while recording, while the 60D, like the 5D Mark II and Rebel T2i, outputs Standard Definition. If your primary shooting mode will be with an external HD monitor such as the SmallHD DP6, the 7D will give you a better signal for frame and focus.

The 5D Mark II remains an awesome stills camera hampered only by an aging autofocus system, and it shoots lovely 24, 25 and 30p video with better low-light performance than any of Canon’s APS-C offerings, including the 60D. Its full-frame sensor allows beyond-cinematic depth of field control. The 5D lacks 50 and 60p modes though, and costs a lot. It’s entirely possible that your heart and photo soul are screaming at you to own a full-frame DSLR, and if that’s the case, of course the 5D Mark II is great. But it’s no longer the king of the video hill unless achieving the shallowest-possible depth of field is your top priority.

If you are specifically interested in video, and stills are a nice feature but not your raison d’être, get the 60D. You’re basically paying the difference between the Rebel and the 60D for manual audio levels, the flip-out screen, and the (occasionally reported) possibility that the 60D is slightly less prone to overheating than the Rebel. It’s a great camera for a great price, and the articulated screen alone is worth it. Again, just say no to the kit lens.

Proof that the universe loves you: as I began to write this, the Canon 60D went on sale at Amazon for $899. Use coupon code BF8JNEEK at checkout.

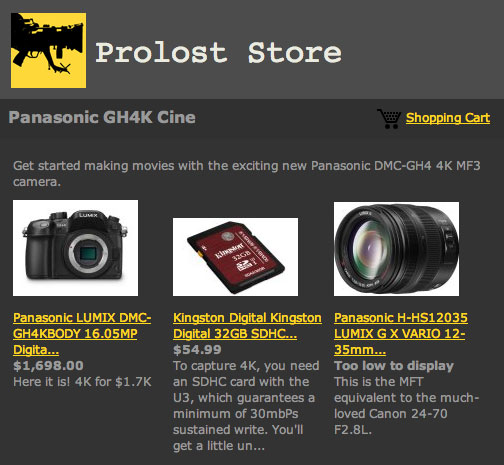

If you’re already a Canon shooter, remember that while the 60D shares batteries with the 5D Mark II and the 7D, it uses SDHC cards instead of CF. I’ve put together a 60D Cine page on the ProLost store to help you get your kit going.

Using a DSLR for video is a compromise. In addition to the technical limitations we’ve discussed here at length, the time-honored form factor of the SLR just wasn’t made for movies. The 60D takes a big step toward fixing this. To me, this matters a lot. The 5D Mark II shot you blew because you couldn’t see the LCD well enough to focus is worth nothing compared to the 60D shot you wrangled from an angle.

Wednesday, December 15, 2010 at 12:22AM

Wednesday, December 15, 2010 at 12:22AM